China’s Belt & Road Initiative: Execution Challenges Part II

• 11 min read

- Brief: Global Economy

Get the Latest Research & Insights

Sign up to receive an email summary of new articles posted to AMG Research & Insights.

“We [had] no choice. Did the rest of the world give us a chance or a choice? If Japan offers us the same, if Europe or the U.S. offers us the same, [there would be] no issue. We are pro-our country, pro-our continent. We are not pro-other foreign country.”

– Aboubaker Omar Hadi, Chairman of the Djibouti Ports and Free Zones Authority, speaking about Djibouti’s participation in the BRI at the Tokyo International Conference on African Development

Like Hadi, “we had no choice” is a common defense among developing countries criticized for their participation in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—a $4 trillion financing strategy to develop a global network connecting China to Asia, Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Latin America by 2049. Criticism and concerns against the BRI have been boiling for the past few years as the developing world has been increasingly dominated by Chinese money funding unsound infrastructure projects (see previous Belt & Road Initiative article).

Among the international community, the BRI is now infamously known as a “debt-trap diplomacy.”1 A harsh accusation that China’s predatory lending deals have left many developing nations ensnared in unsustainable debt and their strategic assets, such as maritime ports and natural resources, vulnerable to Chinese creditors.

Beginning in 2017, Sri Lanka became the poster child of China’s “debt-trap diplomacy” narrative. The revitalized port was theoretically designed to pay for itself as it was promised to attract thousands of ships passing along vital sea lanes in the Indian Ocean. However, it only drew in a little over 30 ships in total during 2012 and almost 200 ships in 2017.2 The promised attraction has still yet to be fulfilled—a common characteristic of completed BRI projects. Struggling to make a meaningful profit and dealing with larger economic issues,3 the Sri Lankan government leased the Chinese-built Hambantota port and 15,000 acres of land surrounding it to the Chinese state-owned giant—China Merchants Port Holdings—for the next 99 years.4

Therefore, since 2018 Chinese President Xi Jinping has been making efforts to downplay the “debt-trap diplomacy” narrative and address rising concerns over the BRI.5 Xi has been stressing to world leaders that the BRI will become more transparent and investment activities will have stricter regulations. Despite the Chinese leader’s reiterations that the BRI will benefit “all of its participants,” promote sustainable growth, and build a community of prosperity, this has not happened consistently since the main purpose of the BRI is to lead economic power back to China.6

THE RISE OF CHINA’S RELATIONAL POWER

While China has been implementing its BRI for only six and a half years, the strategic initiative has been energizing its fast-growing relational power over the developing world in both dependence and connectivity.7 This power may help fuel the rise of China and give Beijing the freedom to secure its future growth. Consider the following:

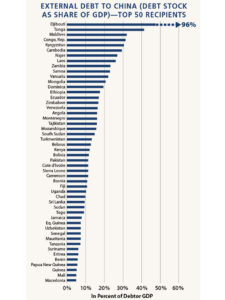

China has been befriending more and more developing nations by pouring billions of dollars into their vulnerable economies. Take Africa where Chinese lending has been exploding. China has already committed $60 billion in loans, financing, equity investments, direct aid and grants into resource-rich African countries.8 Now, 25 out of the 50 most indebted nations to China9 come from the African continent.10 (Click the table image to enlarge.)

China has been befriending more and more developing nations by pouring billions of dollars into their vulnerable economies. Take Africa where Chinese lending has been exploding. China has already committed $60 billion in loans, financing, equity investments, direct aid and grants into resource-rich African countries.8 Now, 25 out of the 50 most indebted nations to China9 come from the African continent.10 (Click the table image to enlarge.)

Chinese investments have also been focusing on BRI energy projects in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) region.11 The construction of high-speed railways and a natural gas pipeline in the region aims to facilitate energy exports to China—essential components to China’s future energy security. Russia remains the largest investor in the region, however, China has taken the lead in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan.12 In Kyrgyzstan, Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) amounted to 20% of GDP compared to Russia’s 15% in 2018.13

China is becoming an important trading partner for many developing countries. The blooming economic relationship between Latin America and China—the region’s second-largest trading partner—is particularly astonishing. Total China-Latin America trade increased from $17 billion in 2002 to a little over $307 billion in 2019—that’s an 18-fold increase!14 China plans to increase that number to $500 billion by 2025.15 And even before the U.S.-China trade war, China’s colossal demand for commodities such as soybeans, copper and oil, allowed them to displace the United States as the biggest trading partner for Brazil, Peru and Chile.16

With Latin America’s economic cycle increasingly tied to Chinese economic activity, an extreme event like the current COVID-19 pandemic could be a new potential source of volatility to an already volatile region.17

BULKING CHINESE STATE-OWNED ENTITIES

So far China has funded all 14,000 BRI projects worth about $700 billion through dedicated Chinese institutions and state-owned banks (SOBs).18 Chinese SOBs such as China Development Bank and Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM) have become popular among the developing world.

Because Chinese SOBs have been willing to take on risks with the BRI, these centralized actors will work for any government—even those with active conflicts like Syria—as the SOBs approach them with flexible requirements and payment terms.19 As the biggest lenders in the world, China Development Bank and CHEXIM lent over $680 billion between 2007 and 2014.20 The next six biggest lenders including the World Bank and Asian Development Bank together provided about $700 billion worth of finance during that same period.21

Furthermore, regardless of whether or not Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are popular among the international community, they have been dominating and gaining exclusive access to BRI projects. Chinese SOEs have been helping developing countries build their infrastructure with Chinese materials, labor, and expertise all while reducing the supply glut at home (see “Special Report: China’s Gordian Knot”).22

Xi has been pushing for “bigger and stronger” Chinese SOEs so China can remain competitive in the free market system.23 Therefore, policy strategies like the BRI have been giving China that very opportunity. In 2000, the Fortune Global 500 list24 included only 10 Chinese firms of which 9 were SOEs.25 Almost two decades later, Chinese companies outnumbered the United States on the latest Global 500 list. The 2019 Global 500 featured 129 Chinese companies of which 82 were SOEs compared to 121 U.S. firms26—the first time the United States has lost its lead position in international big business since WWII.27

WE HAD NO CHOICE

Despite being fully aware that the BRI has not been such a “win-win” deal, countries are still accepting China’s handouts. Last year, the Philippines signed more than $18 billion worth of BRI agreements including Chinese grants that could help with the government’s ongoing war against drugs.28 However, the Filipino government stressed that “the President, many Filipinos…would make sure there is mutual respect for sovereignty. That is what we should maintain as good friends.”29

Like the Philippines, the rest of the developing world is desperate for infrastructure investments to keep their promise of pursuing global challenges such as poverty and climate change.30 So, their “we had no choice” defense seems perfectly credible because the rest of the world has been too busy investing in the United States and the rest of the developed world. Japan—one of the world leaders in outward FDI—has been focusing Japanese FDI in Europe and North America for the past two decades.31

While China has been bearing investment gifts to the developing world, the United States’ global FDI footprint has been on a slow recovery from the 2008 Great Recession. More recently, U.S. multinational enterprises (MNEs) have been retracting overseas investments and making the most out of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) reform of 2017.32

As long as developing countries desire development and growth opportunities, and China continues to aspire to become the wealthiest economy in the world, the BRI will continue to move forward despite the execution challenges China has been facing. Beijing is in it for the long game, so present setbacks such as its sluggish economy and the COVID-19 pandemic will not retract it from its BRI agenda. China will continue to take steps to secure its future growth and ascent as the most powerful economy in the world by 2050.

Notes

-

Lindberg, Kari and Tripti Lahiri. From Asia to Africa, China’s “Debt-Trap Diplomacy” was Under Siege in 2018. QUARTZ, 28 Dec. 2018, https://qz.com/1497584/how-chinas-debt-trap-diplomacy-came-under-siege-in-2018/.

-

Abi-Habib, Maria. How China Got Sri Lanka to Cough Up a Port. The New York Times, 25 Jun. 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/25/world/asia/china-sri-lanka-port.html.

-

Moramudali, Umesh. Is Sri Lanka Really a Victim of China’s “Debt Trap”? The Diplomat, 14 May 2019, https://thediplomat.com/2019/05/is-sri-lanka-really-a-victim-of-chinas-debt-trap/.

-

Abi-Habib, Maria. How China Got Sri Lanka to Cough Up a Port. The New York Times, 25 Jun. 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/25/world/asia/china-sri-lanka-port.html.

-

Xinhua. Xi Gives New Impetus to Belt and Road Initiative. China Daily, 28 Aug. 2018, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201808/28/WS5b84994fa310add14f388114.html.

-

Xinhua. Xi Gives New Impetus to Belt and Road Initiative. China Daily, 28 Aug. 2018, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201808/28/WS5b84994fa310add14f388114.html; Jiangtao, Wu, Zheng, and Zhenhua Lu. Chinese President Xi Jinping Tries to Stem Rising Chorus of Doubts Over Belt and Road Initiative. South China Morning Post, 26 Apr. 2019, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3007892/chinese-president-xi-jinping-tries-stem-rising-chorus-doubts.

-

Moyer, Jonathan. Measuring and Modeling the Rise of China. CCUSC Jackson/Ho China Forum and the Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures, 26 Feb. 2020.

-

Citi GPS. China’s Belt and Road at Five: A Progress Report. Citi Group, Dec. 2018, https://www.citivelocity.com/citigps/chinas-belt-road-initiative/.

-

In terms of debt to China as a share of a nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

-

Horn, Sebastian, et al. “China’s Overseas Lending.” KIEL Institute for the World Economy, Jun. 2019, https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/200198/1/1668908891.pdf.

-

The CIS region includes Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan; Citi GPS. China’s Belt and Road at Five: A Progress Report. Citi Group, Dec. 2018, https://www.citivelocity.com/citigps/chinas-belt-road-initiative/.

-

Citi GPS. China’s Belt and Road at Five: A Progress Report. Citi Group, Dec. 2018, https://www.citivelocity.com/citigps/chinas-belt-road-initiative/.

-

Citi GPS. China’s Belt and Road at Five: A Progress Report. Citi Group, Dec. 2018, https://www.citivelocity.com/citigps/chinas-belt-road-initiative/.

-

China’s Engagement with Latin America and the Caribbean. Congressional Research Service, 11 Apr. 2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/IF10982.pdf; Elmer, Keegan. Latin America Trade Grows as China and US Tussle for Influence. 28 Jul. 2019, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3020246/latin-america-trade-grows-china-and-us-tussle-influence.

-

Cooperation Plan (2015–2019). China-CELAC Forum, 23 Jan. 2015, http://www.chinacelacforum.org/eng/zywj_3/t1230944.htm.

-

Citi GPS. China’s Belt and Road at Five: A Progress Report. Citi Group, Dec. 2018, https://www.citivelocity.com/citigps/chinas-belt-road-initiative/.

-

Citi GPS. China’s Belt and Road at Five: A Progress Report. Citi Group, Dec. 2018, https://www.citivelocity.com/citigps/chinas-belt-road-initiative/; Lopez-Calva, Luis F. How Will COVID-19 Affect Economies of Latin America & the Caribbean? Inter Press Service News Agency, 12 Mar. 2020, https://www.ipsnews.net/2020/03/will-covid-19-affect-economies-latin-america-caribbean/.

-

China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Entering A Cooling-Down Phase. BCA Research, 7 Jan. 2019.

-

Hillman, Jonathan. China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Five Years Later. Center for Strategic & International Studies, 25 Jan. 2018, https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-five-years-later-0.

-

Soutar, Robert. China Becomes World’s Biggest Development Lender. China Dialogue, 25 May 2016, https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/8947-China-becomes-world-s-biggest-development-lender.

-

Soutar, Robert. China Becomes World’s Biggest Development Lender. China Dialogue, 25 May 2016, https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/8947-China-becomes-world-s-biggest-development-lender.

-

Cai, Peter. Understanding China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Lowy Institute for International Policy, Mar. 2017, https://think-asia.org/bitstream/handle/11540/6810/Understanding_Chinas_Belt_and_Road_Initiative_WEB_1.pdf?sequence=1.

-

Cai, Jane. Why China’s Subsidized State-owned Enterprises Anger US, Europe – and its own Private Companies. South China Morning Post, 21 Feb. 2019, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/2184707/why-chinas-subsidised-state-owned-enterprises-anger-us-europe.

-

The world’s 500 largest companies by revenue.

-

Hillman, Jonathan. China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Five Years Later. Center for Strategic & International Studies, 25 Jan. 2018, https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-five-years-later-0.

-

Top 10 Chinese Companies in Fortune Global 500. China Daily, 29 Jul. 2019, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201907/29/WS5d3e2961a310d83056401650.html.

-

Colvin, Geoff. It’s China’s World. Fortune, 22 Jul. 2019, https://fortune.com/longform/fortune-global-500-china-companies/.

-

Lee, Lynn and Phila Siu. Philippines Open for Business with China but Stands Firm on Insisting Beijing Respects its Sovereignty: Trade Secretary. South China Morning Post, 25 Apr. 2019, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/geopolitics/article/3007711/philippines-open-business-china-stands-firm-insisting-beijing.

-

Lee, Lynn and Phila Siu. Philippines Open for Business with China but Stands Firm on Insisting Beijing Respects its Sovereignty: Trade Secretary. South China Morning Post, 25 Apr. 2019, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/geopolitics/article/3007711/philippines-open-business-china-stands-firm-insisting-beijing.

-

Hurley, John, et al. “Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective.” Journal of Development, vol. 3, no. 1, 2019, pp. 139-175, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334096436_Examining_the_debt_implications_of_the_Belt_and_Road_Initiative_from_a_policy_perspective.

-

Huijie, Gu. “Outward Foreign Direct Investment and Employment in Japan’s Manufacturing Industry.” Journal of Economic Structures, 16 Oct. 2018, https://journalofeconomicstructures.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40008-018-0125-z#article-info.

-

Global Foreign Direct Investment Slides for Third Consecutive Year. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 12 Jun. 2019, https://unctad.org/en/pages/newsdetails.aspx?OriginalVersionID=2118

Chart Source: Horn, Sebastian, Reinhart, Carmen, and Christoph Trebesch. China’s Overseas Lending. NBER Working Paper No. 26050, revised May 2020; Brookings.

This information is for general information use only. It is not tailored to any specific situation, is not intended to be investment, tax, financial, legal, or other advice and should not be relied on as such. AMG’s opinions are subject to change without notice, and this report may not be updated to reflect changes in opinion. Forecasts, estimates, and certain other information contained herein are based on proprietary research and should not be considered investment advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any particular security, strategy, or investment product.

Get the latest in Research & Insights

Sign up to receive a weekly email summary of new articles posted to AMG Research & Insights.