China’s Belt & Road Initiative: Execution Challenges Part I

• 13 min read

- Brief: Global Economy

Get the Latest Research & Insights

Sign up to receive an email summary of new articles posted to AMG Research & Insights.

“Let us establish a new win-win partnership for all mankind. Let prosperity, fairness and justice spread across the world.”

– Xi Jinping, president, People’s Republic of China

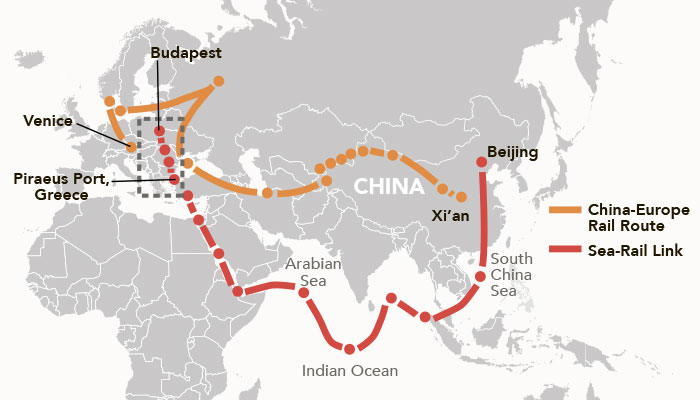

President Xi Jinping introduced China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to the world in 2013. Xi promised a “win-win” partnership encouraging peaceful coexistence, cooperative investment and shared economic growth for all who participated. Countries around the world bought into Xi’s aggressive plan to build a modern trade network connecting China to Asia, Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America. But now, the BRI is entering a new narrative. It’s considered globally as a Chinese hegemony over the developing world.

Several countries are resisting the BRI because of their concern about China’s possibly excessive influence on their economies. Thus, they are reconsidering investment commitments, renegotiating contracts and canceling infrastructure projects. For example, Bangladesh decided to collaborate with Japan, instead of China, to build its first deep water port in 2017.1 That same year, Nepal canceled a BRI deal to build a hydropower plant.2

Global concerns appear to be rising for all the right reasons. For the past six years, the BRI has not been such a peaceful development and “win-win” cooperation like President Xi Jinping promised the world it would be.

Nevertheless, many developing nations have been welcoming Chinese investments because they’ve been hungry for any opportunities to develop and grow. To date, over 150 BRI cooperation agreements with more than 100 countries and about 30 international organizations have been signed so far.3 Developing Asia alone requires over $20 trillion in infrastructure investments to adapt to climate change and maintain growth for the next decade.4 In particular, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations5 (ASEAN) has become the heart of the BRI. Chinese companies’ familiarity with and confidence in ASEAN is reflected in BRI investment commitments, which account for almost 50% of total project announcements compared to about 30% for other BRI regions.6

Thanks to the BRI, China’s economic relationship with these nations is transforming from being just trade partners to an investor in their economies. The BRI is building powerplants, natural gas pipelines, intercontinental highways, high-speed railroads, strategic seaports, modernized airports and new centers of commerce throughout the developing world. In under seven years, signed BRI contracts amount to an extravagant $700 billion, where over $400 billion has already been completed.7

So Xi is determined to successfully complete the BRI, which may help transform China from a middle-income to an upper-income economy; however, criticisms from the international community needed to be addressed. At the 2018 symposium marking the fifth anniversary of the BRI, Xi stressed the need to:

- Deliver real benefits to local people through BRI projects.

- Have stricter regulations on BRI investment activities.

- Pay higher attention to reducing BRI risks overseas.8

These priorities were created in efforts to resolve the following BRI issues.

LOCAL NEED IS MISSING FROM SOME BRI PROJECTS

Some BRI projects are not supported by local economic needs but by remote Chinese motivations. Thus, some BRI projects aren’t paying for themselves.

Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport is the world’s emptiest international airport and is a classic example. Located near the Sri Lankan port town of Hambantota, this over $200 million jewel was financed by China and built with Chinese expertise in a wave of BRI infrastructure projects in the area (e.g. cricket stadium, highway, and deep-water port).9 As the second-largest airport in Sri Lanka, the Mattala was designed to attract a million passengers every year.

These passengers would transform Hambantota, which is coincidentally located only a couple miles away from a vital Indian Ocean sea lane transporting over 80% of Chinese oil imports, into a vibrant modern city and tourism hub.10 Meanwhile, China could secure this strategic port town through its growing financial influence.

But sadly, the airport has been receiving more elephants and other wild animals than travelers since its launch in 2013.11 Less than a dozen travelers pass through its terminal every day.12 Elephant dung and bills are piling up as Sri Lanka tries to repay China more than $20 million a year with disappointing revenues close to $300,000 annually.13 This begs the question: Is this really a “win-win” deal?

DEVELOPING NATIONS ARE PILING ON CHINESE DEBT

China has been the biggest lender for BRI projects. It has even developed dedicated institutions to support BRI projects, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and Silk Road Fund. As a result, other developing nations are also piling on Chinese debt.

Take Djibouti. This tiny African nation has been known for its love of tea and proximity to the world’s busiest sea lanes. However, the latest spotlight has been on its alarming debt crisis because Djibouti has been on a development spree and China is engineering, building and financing most of it.

A $4 billion Chinese-built railway now links the Ethiopian capital of Addis Ababa to the Djiboutian capital, Djibouti City.14 This roughly 700 km high-speed line cuts travel time for both passengers and cargo from days to hours.15 While the line was completed in 2017, the Chinese will be operating it for five more years before handing it over to the locals – a common arrangement for BRI projects.16

In 2018 China and Djibouti launched the first phase of construction on the $3.5 billion Djibouti International Free Trade Zone (DIFTZ).17 The DIFTZ will become Africa’s largest free trade zone and logistics hub in less than a decade and will connect Djibouti’s main ports to crucial Chinese trade routes. The almost 12,000-acre zone will be operated by Djibouti and several Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) such as China Merchants Group.18 Meaning, China will have influence over the DIFTZ.

The development doesn’t end there. Djibouti plans to invest $4 billion in a gas pipeline that will transport Ethiopian gas to a Djiboutian export terminal and then to China via the Suez Canal.19 It will also let China build two new airports worth nearly $600 million.20

Djibouti’s dream to transform into a middle-income country through the Chinese BRI is turning into a debt nightmare. Its debt to China is now worth almost 100% of its gross domestic product (GDP)21 – that’s nearly $2 billion.22 But Djibouti is not alone. African nations have borrowed more than $100 billion from China in the past two decades.23 Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Maldives, Mongolia, Montenegro, Pakistan and Tajikistan are also in the same sinking boat of Chinese debt.24

CHINESE INVESTMENT OFTEN HAS STRINGS ATTACHED

Developing countries thought Chinese investments would help evolve their economies, but it can come at a price.

In Greece, a Chinese shipping SOE giant – China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) – revitalized then took control of the Athens’ port of Piraeus. Beginning in 2005, the Piraeus port saw a drop-in container volume amid the growing debt-crisis in cash-strapped Greece.25 Unexpectedly, COSCO threw Athens an economic lifeline and sealed an almost $6 billion deal in 2008 to build a terminal and renew the port.26

Since COSCO’s involvement, the Piraeus has become the second largest port in the Mediterranean and one of the most productive ports in the world. The port ascended from 93rd to 30th in global ranking as its container volumes jumped from almost 1 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs)27 in 2010 to nearly 5 million TEUs less than a decade later.28

With this successful revitalization, Athens has a productive Greek port that’s owned by China because it has been relying on privatizations to bail out its sinking economy since 2010.29 As a result, COSCO offered a sole bid of $400 million in 2016 and became the official operator and owner of the port.30 Now, the Piraeus port serves China as a southern gateway to Europe for Chinese container vessels traveling through the Suez Canal.

SECURITY OF BRI NATIONS MAY BE THREATENED

National security of participating BRI nations may be threatened as China implements Chinese national standards for 5G in countries along its Belt and Road. As of 2019, Chinese tech giants like Huawei and ZTE were involved in more than 50 5G projects in over 30 countries.31

Take Huawei, the world’s biggest telecommunications company and number two smartphone maker. This Chinese powerhouse has been defending itself against growing scrutiny from around the world as its customer base expands.

In Britain – one of the most important markets for Huawei – U.K. officials are becoming more concerned about the safety of Huawei’s telecommunications equipment. In late 2018, a British lab flagged Huawei’s gear with software issues that could create security holes that could easily be hacked and exploited.32

Last year, Huawei – the dominant telecommunications company in African markets – was accused of helping African governments spy on political opponents. Huawei employees allegedly used the company’s technology and products to support domestic spying.33

In Zambia, Chinese technicians intercepted encrypted messages and tracked down opposition bloggers using cellular data.34 Uganda has a similar story. Huawei engineers used spyware to help cut short planned street rallies and arrest political sensation, Bobi Wine, and dozens of his opposition supporters.35

Huawei has denied all allegations and continues to rise in global markets.

CONCLUSION

The BRI does not appear to be the “win-win” cooperation like Xi promised. Many developing nations are struggling to benefit from the BRI, while China continues to follow its vigorous agenda to complete its modern Silk Road in time for the People’s Republic of China’s 100th anniversary in 2049. However, you can call the past six years of the BRI a “trial-and-error” phase. China is adjusting its BRI tactics to soothe concerns, continue solid cooperation of Belt and Road countries, ensure the BRI’s success and most importantly, secure China’s future growth.

Notes

-

Rolland, Nadege. Reports of Belt and Road’s Death are Greatly Exaggerated. Foreign Affairs, 29 Jan. 2019, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2019-01-29/reports-belt-and-roads-death-are-greatly-exaggerated.

-

Rolland, Nadege. Reports of Belt and Road’s Death are Greatly Exaggerated. Foreign Affairs, 29 Jan. 2019, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2019-01-29/reports-belt-and-roads-death-are-greatly-exaggerated.

-

United States. Senate Committee on Finance. Subcommittee on International Trade, Customs and Global Competitiveness. Testimony, 12 Jun. 2019, https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Carolyn%20Bartholomew%20-%20BRI%20Testimony.pdf.

-

Hillman, Jonathan. China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Five Years Later. Center for Strategic & International Studies, 25 Jan. 2018, https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-five-years-later-0.

-

ASEAN includes Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

-

Citi GPS. China’s Belt and Road at Five: A Progress Report. Citi Group, Dec. 2018, https://www.citivelocity.com/citigps/chinas-belt-road-initiative/.

-

China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Entering A Cooling-Down Phase. BCA Research, 7 Jan. 2019.

-

Xinhua. Xi Gives New Impetus to Belt and Road Initiative. China Daily, 28 Aug. 2018, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201808/28/WS5b84994fa310add14f388114.html.

-

Larmer, Brook. What the World’s Emptiest International Airport Says About China’s Influence. The New York Times, 13 Sept. 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/13/magazine/what-the-worlds-emptiest-international-airport-says-about-chinas-influence.html.

-

Larmer, Brook. What the World’s Emptiest International Airport Says About China’s Influence. The New York Times, 13 Sept. 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/13/magazine/what-the-worlds-emptiest-international-airport-says-about-chinas-influence.html.

-

Hope, Allison. This $200 Million Airport Sees an Average of 7 Passengers a Day. Conde Nast Traveler, 10 Oct. 2017, https://www.cntraveler.com/story/this-200-million-dollar-airport-sees-an-average-of-7-passengers-a-day.

-

Larmer, Brook. What the World’s Emptiest International Airport Says About China’s Influence. The New York Times, 13 Sept. 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/13/magazine/what-the-worlds-emptiest-international-airport-says-about-chinas-influence.html.

-

Larmer, Brook. What the World’s Emptiest International Airport Says About China’s Influence. The New York Times, 13 Sept. 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/13/magazine/what-the-worlds-emptiest-international-airport-says-about-chinas-influence.html.

-

Jeffrey, James. On Board the Chinese-built Ethiopia to Djibouti Train, a Lesson in Compromise for Clashing Cultures. South China Morning Post, 12 Dec. 2018, https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/travel/article/2177559/board-chinese-built-ethiopia-djibouti-train-lesson; Ethiopia – Djibouti High Speed Railway Finally Completed. CGTN, 10 Jan. 2017, https://africa.cgtn.com/2017/01/10/44393/.

-

Clemoes, Charlie. Cities on the New Silk Road: Djibouti City. TOPOS, 3 Jun. 2019, https://africa.cgtn.com/2017/01/10/44393/.

-

Jeffrey, James. On Board the Chinese-built Ethiopia to Djibouti Train, a Lesson in Compromise for Clashing Cultures. South China Morning Post, 12 Dec. 2018, https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/travel/article/2177559/board-chinese-built-ethiopia-djibouti-train-lesson.

-

Dahir, Abdi. Thanks to China, Africa’s Largest Free Trade Zone Has Launched in Djibouti. QUARTZ, 9 Jul. 2018, https://qz.com/africa/1323666/china-and-djibouti-have-launched-africas-biggest-free-trade-zone/.

-

Dahir, Abdi. Thanks to China, Africa’s Largest Free Trade Zone Has Launched in Djibouti. QUARTZ, 9 Jul. 2018, https://qz.com/africa/1323666/china-and-djibouti-have-launched-africas-biggest-free-trade-zone/.

-

Maasho, Aaron and Mark Potter. Ethiopia and Djibouti Sign Deal to Build Gas Pipeline. Reuters, 17 Feb. 2019, https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-ethiopia-djibouti-gas/ethiopia-and-djibouti-sign-deal-to-build-gas-pipeline-idUKKCN1Q6071.

-

Lo, Kinling. From Rail and Airports to Its First Overseas Naval Base, China Zeroes in on Tiny Djibouti. South China Morning Post, 21 Nov. 2017, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy-defence/article/2120713/rail-and-airports-its-first-overseas-naval-base-china.

-

Gandhi, Dhruv. Figure of the Week: China’s ‘Hidden’ Lending in Africa. Brookings, 10 Jul. 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2019/07/10/figure-of-the-week-chinas-hidden-lending-in-africa/.

-

Djibouti GDP is in terms of 2018 data. Source: GDP (current US$) – Djibouti. The World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=DJ.

-

Damon, Arwa and Swails, Brent. China and the United States Face Off in Djibouti as the World Powers Fight for Influence in Africa. CNN, 27 May 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/05/26/africa/china-belt-road-initiative-djibouti-intl/index.html.

-

Hurley, John, Morris, Scott, and Portelance, Gailyn. “Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective.” Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, vol. 3, no. 1, 2019, pp. 139-175, https://systems.enpress-publisher.com/index.php/jipd/article/viewFile/1123/871.

-

People’s Daily Online. Chinese Company Revitalizes Largest Port in Greece. The Belt and Road News Network, 18 Apr. 2019, http://en.brnn.com/n3/2019/0418/c414872-9568741.html.

-

Maltezou, Renee. Greece’s Piraeus Port Seals Deal with Cosco. Reuters, 10 Oct. 2008, https://www.reuters.com/article/piraeusport-cosco/update-1-greeces-piraeus-port-seals-deal-with-cosco-idUSLA27344320081010.

-

One TUE is equal to a standard 20’ long, 8’ wide and 8’ tall shipping container.

-

Top 50 World Container Ports. World Shipping Council, http://www.worldshipping.org/about-the-industry/global-trade/top-50-world-container-ports; People’s Daily Online. Chinese Company Revitalizes Largest Port in Greece. The Belt and Road News Network, 18 Apr. 2019, http://en.brnn.com/n3/2019/0418/c414872-9568741.html.

-

Greek Bailout Crisis in 300 Words. BBC, 20 Aug. 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-45245969.

-

Koutantou, Angeliki. China’s Cosco Makes Improved $400 Million Bid for Greece’s Largest Port. Reuters, 20 Jan. 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-greece-privatisation-port-idUSKCN0UY2EW.

-

United States. Senate Committee on Finance. Subcommittee on International Trade, Customs and Global Competitiveness. Testimony, 12 Jun. 2019, https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Carolyn%20Bartholomew%20-%20BRI%20Testimony.pdf.

-

Woo, Stu. Huawei Says Its Gear is Safe; U.K. Officials Aren’t Sure Anymore. The Wall Street Journal, 23 Dec. 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/huawei-says-its-gear-is-safe-u-k-officials-arent-sure-anymore-11545577200?mod=article_inline.

-

Parkinson, Joe, Bariyo, Nicholas, and Josh Chin. Huawei Technicians Helped African Governments Spy on Political Opponents. The Wall Street Journal, 15 Aug. 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/huawei-technicians-helped-african-governments-spy-on-political-opponents-11565793017.

-

Parkinson, Joe, Bariyo, Nicholas, and Josh Chin. Huawei Technicians Helped African Governments Spy on Political Opponents. The Wall Street Journal, 15 Aug. 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/huawei-technicians-helped-african-governments-spy-on-political-opponents-11565793017.

-

Parkinson, Joe, Bariyo, Nicholas, and Josh Chin. Huawei Technicians Helped African Governments Spy on Political Opponents. The Wall Street Journal, 15 Aug. 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/huawei-technicians-helped-african-governments-spy-on-political-opponents-11565793017.

This information is for general information use only. It is not tailored to any specific situation, is not intended to be investment, tax, financial, legal, or other advice and should not be relied on as such. AMG’s opinions are subject to change without notice, and this report may not be updated to reflect changes in opinion. Forecasts, estimates, and certain other information contained herein are based on proprietary research and should not be considered investment advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any particular security, strategy, or investment product.

Get the latest in Research & Insights

Sign up to receive a weekly email summary of new articles posted to AMG Research & Insights.